Alumnus

Profile:

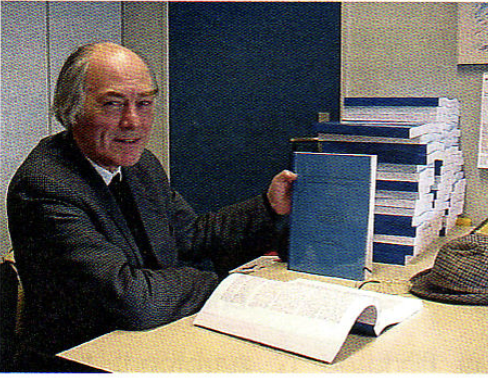

Jim Ward; B.Sc. and Ph.D. (Edinburgh,1953, 1956),

M.A. and D.Litt. (Leiden, 1995, 2001)

In these austere times it seems appropriate to

refer briefly to an earlier time when even more austerity was the order of the

day. In 1949 when I went from Peebles High School to Edinburgh University to study

Chemistry, food, clothing and petrol were still rationed.

In these austere times it seems appropriate to

refer briefly to an earlier time when even more austerity was the order of the

day. In 1949 when I went from Peebles High School to Edinburgh University to study

Chemistry, food, clothing and petrol were still rationed.

Parritch

and auld claes was a saying that was reality for many people. Bread and

potatoes, which had been freely available during the war, were rationed; bread

in 1946, potatoes in 1947. National Service was in force. There was everywhere

a lack of colour; in people’s shoddy clothing and in the drab appearance of

many of Edinburgh’s public buildings. Students whom I knew told me in advance

about the gloomy corridors extending in from the main entrance of the Chemistry

Department, now Joseph Black Building; about the interior bare brick walls,

unpainted because paint apparently was a fire hazard; and about the lack of

windows in some of the rooms. I still visit the department once or twice a

year, using Google Earth now to get there. The cameras don’t show me if the

interior has been brightened up. I can only hope so.

But the

heart of the Chem. Dept. lay in the students’ labs. They were lit through

skylights, and by the occasional unintentional blaze. Personal safety had a

very low priority with us. We seldom if ever wore safety specs, the fume

cupboards were ineffectual, and so we soon became used to stinks and bangs. As

undergraduates our apparatus was of glass and corks, and our dream was to have

Quickfit glassware, like the research

students had. In our first year, Chemistry, Physics and Maths were obligatory

subjects; then as now, I assume. The latter two were taught in town, near the

Old Quadrangle, and that required students to travel up and down from

Corstorphine by tram. A boring journey, and it cost us money. Maths broke many

a chemistry student’s heart. It was a pure math course, but I heard that since

then concessions have been made. In my study I combined Chemistry with Physics

II and Biochemistry I.

An

advantage of austerity was that there were few distractions from studying, and

so without a hitch I graduated B.Sc. in 1953, and in 1956 Ph.D., with a thesis

on azulene chemistry. The Chem. Soc. London republished some of it not long

ago. Quel honneur! We did get Quickfit glassware at this stage, but we had to

purify our own solvents and make our own starting materials; it was valuable

training. My supervisor was Dr W. H. (Willie) Stafford, who had earned his Ph.

D. under Professor Neill Campbell (1903-1996). To both of them, now deceased, I

am eternally grateful. What they had in common was great enthusiasm for chemistry. Back then I

worked as a demonstrator in the Organic

lab and in Dr Chrissie Miller’s analytical lab. Dr Miller was born in 1899, and

among everything else that I learned from her was punctuality. We remained

friends, writing each other at intervals until she died in 2001.

As a

demonstrator I earned £120/annum (that’s right, per annum). So like some other

Ph. D. students I stayed working till late most evenings. Twice a week or so I

missed the last bus, intentionally I think now, down to Portobello High Street,

near where I lodged with my aunt. My favourite memory of Edinburgh was of

walking from KB to Portobello through Duddingston on clear winter or moonlit

nights. The streets were deserted. With the moon in front of me and Arthur’s

Seat towering behind me, it was like a scene from “Kidnapped”, and I was playing

Davy Balfour.

On leaving

Edinburgh I was awarded fellowships by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation,

whose head office is still in Bonn, and later by the German Research Foundation

(DFG). I was deeply moved when in September 1956 Neill Campbell came down to

Leith to see me off on the ship to Hamburg. I spent the next five years, first

in Berlin for a year (Prof. F. Weygand) and then Heidelberg (Profs G. Wittig

and O. Th. Schmidt). Germany was an unforgettable experience for me. My advice

to young women and men is, if you wish to study or do research abroad, choose

Europe! You will have to apply for money and prepare about a year before

graduating or applying.

There was

no lack of work for research chemists in the UK on my return in 1961. I took up

a post in Unilever Research Division, first in England, and soon after at

Unilever Research Lab ( URL) Vlaardingen in the Netherlands. Total staff there

was about 1200. The three organic chemistry sections employed about 50 people,

and there were three similar biochemistry sections. In 1969 I was made section

leader of Organic Chemistry II. Until 1989 my work, much of which has been published,

was mostly on natural compounds in tropical vegetable oils, and in the organic

synthesis of glycerides and flavour compounds.

I must say, however, the nature of the work at

URL has changed since then. Long before 1989

Research Division had become top heavy. At the age of 58 I was one of

several hundred scientists in management throughout the Unilever concern who

received fairly generous financial offers, on condition that we accept early

retirement. I accepted. In 1956, on leaving KB for the last time, I had asked

myself, what now?

In 1989 I

asked myself the same question again. My whole professional adult life until

then had been spent doing research in organic chemistry. That limits the advice

I can give any Chemistry student or teacher, but if your ambition ultimately is

to do research of any kind, then read on. As an undergraduate or research

student, you belong, I’m told, to a generation that can expect to live to about

100 (cf. Dr Chrissie Miller, above). The French chemist M. E. Chevreul (1786-1889)

still worked in his lab at that age. But you won’t. So what are you going to do

in the thirty or forty years after you retire in the 2050’s or 60’s? That is

similar to the question I faced in 1989.

Research

and experimental chemistry may be ruled out for you, but you could do something

like I did. I have always been interested in History. At Edinburgh, Professor

James Kendall (1889-1978) encouraged that interest in his students. His exams

had an optional question on the History of Chemistry. So in 1989 I enrolled as

a first year student at Leiden University. I learned to specialise in the

history not of Chemistry but of Late Medieval Holland, graduating M. A. in 1995.

After a further six years of archival research, with Professor Wim Blockmans as

advisor, I graduated D. Litt in 2001, with a thesis on the diets of the States

of Holland in the years 1506 to1515 (N.B. the other kind of diet). Since then I

have continued to do research and publish articles related to my two history

theses.

If you think history is bunk then, perhaps in

thirty years’ time on recalling my story, you might wish to prepare yourself

for other research, other employment, other interests. But for now if you are nearing

graduation, you should plan with care your future career whether as a chemist

in research, in teaching, or in other employment.

Not only

for one year ahead but for five years. Be realistic. Know thyself! Update your

plan regularly. At suitable moments during early interviews ask the bosses in

industry whether their companies provide regular in-house managerial training

and career advice. Big companies certainly do. Ask yourself at times whether

you are happy in what you are doing, and if you are making progress towards

your goals. Act accordingly, and remember: time flies. At Peebles High School

in my schooldays there was an inscription attributed to King George V: It is to

the Young that the Future belongs. Make the most of it.